‘The American Dream in Reverse,’ by Rob Couteau

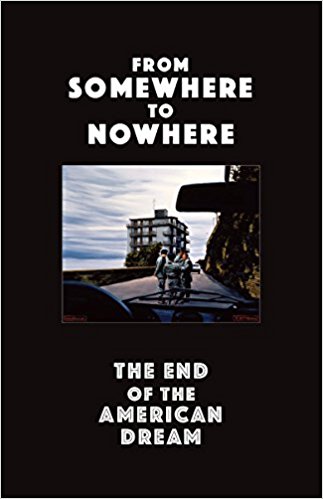

An excerpt from the fictional picaresque, WONDER, published in 'From Somewhere to Nowhere: The End of the American Dream' (NY: Autonomedia; 2017)

In the spring of ’81, my friend Drew found an apartment in the Lower East Side, and he asked if I wanted to share it. A fifth-floor walk-up on East Eleventh, it was moderately priced, so

we decided to grab it.

At once, we set about to renovate the place: slapping up sheetrock, coating the floor with polyurethane,

and sealing the cracks along the baseboards. The latter

task was of special import, because so many roaches came crawling out at night that they would have walked across our faces if we hadn’t positioned

the bed legs in sardine cans filled

with kerosene.

The flat overlooked a school yard across the

street: a big open space with trees flanking the eastern and western edges of a cyclone fence, so you

could almost imagine that you weren’t sandwiched into a claustrophobic Manhattan maze. Downstairs, there was a jewelry store, but Drew said it was

really a money-laundering joint, filled with a slithering lot of repugnant reptiles with thick gold chains hanging from beefy

necks. Shortly after we moved in, it was busted and shut down by the Feds.

The building next door, toward First Avenue,

featured an Italian American club, and the cigar-chomping man who ran it, a short stout

fellow named Freddie, was our landlord. Although we didn’t realize it at the time,

the real owner, a mobster, was locked up in a federal penitentiary, and Freddie

was fronting for him.

Freddie owned an overweight mastiff named Peggy, a beast that was so obese that it took ten minutes for it to climb the three cement steps that led into the club – with her stomach dragging along each step. The

men inside fed it filet mignon, lasagna, and spaghetti with mushrooms and tomato sauce. Peggy devoured everything without the slightest hesitation. Her favorite toy was a regulation-sized football, which she munched as easily

as another dog might chew on a rubber ball.

Freddie seemed to take an instant liking to us, and especially to me for some reason. At first, we thought it was because, coming from Gravesend, Drew and I knew how to talk respectfully and in a certain down-to-earth manner to men such as Freddie, even though it was obvious that we weren’t quite like Freddie, being a bit more schooled and polished. But we never behaved pretentiously or felt awkward in his presence: something he appreciated

since there were so many yuppies scrambling to find flats in the neighborhood, which was rapidly changing. But as we soon discovered,

Freddie’s gregariousness had other, more sinister roots.

A few months after we moved in, I lost my job as a photographer’s

assistant, so I was forced to quickly find something else. From that moment on, we suspected that Freddie

had planted a bug in our flat, because

he always seemed to know when things were tight. Whenever I was

about to have trouble paying the rent, he’d appear with some work.

Eventually, he hired me as his right-hand man, and together we’d renovate apartments so that he could charge the yuppies

even more.

A typical day with Freddie would

begin in his flat, the only one on the ground floor, where we’d devour a lumberjack breakfast of three or four eggs each, with ham, sausage, bacon, or all three, and topped with an espresso that would, as he said, “stiffen the hair on your nuts.” All this chez Bonzet, a Sicilian word meaning “little

fruit,” for Bonzet – the only nonmobbed-up man around, as we later learned – was over

three hundred pounds.

A fair haired, blue eyed, and slightly nervous fellow, Bonzet – or Jimmy – enjoyed the simple things, such as

relaxing in the sun in his folding chair, devouring an enormous spread, or chatting about whatever nonsense happened to be the order of the day. Jimmy also possessed a delightful sense of humor, and, more than anything, he loved to laugh. Only something stressful,

such as Freddie’s snide comments, endless ribbing,

or gruff commands could flip his

switches and trigger his more anxious,

jittery side.

This trait also formed

a keynote in the personality of Bonzet’s younger brother,

Rocco: a diminutive fellow with a blond crew cut and a big toothy grin. Besides being high-strung, Rocco was also a bit manic. On sunny days, he’d continually sweep

outside the club with an oversized straw broom,

twitching nervously and jabbering like a cockatoo. Rocco could never remain still; he hopped about like a sparrow searching

for

birdseed, whirling his broom over the same spot that

he’d swept just seconds before. But like Bonzet,

he always exhibited a palpable warmth and gregariousness, and so Rocco and I also quickly

bonded.

Well fortified by Bonzet’s cooking, Freddie

and I would clamber up the slate steps inside the

building, where he’d lead me into some ancient, dilapidated tenement. These were

the

same apartments that the nineteenth-century immigrants had lived in, gaining their first foothold in America. And there we were, Drew and I, college-educated guys from solid, middle-class families, and what the fuck is wrong with you kids? It’s as if your grandparents’ American dream is running in

reverse! And how on earth can you afford such astronomical prices?

People are paying seven hundred bucks a month for these dumpy, roach-infested holes! Freddie would exclaim, all the while insulting us, berating us, and puzzling over why we’d let him take such advantage of

us.

A classic Freddie rant, it was the kind of thing he pulled on everyone. He loved to break your balls; that was just Freddie. He was also crowned with a Napoleon complex,

not just because of his petite stature but for some other, more mysterious reason: something I never quite fathomed,

and which I never asked about, but I suspect it had something to do with the father that he never once mentioned.

At the beginning of each day we’d bust hump, perhaps down on our hands and knees as he taught me how to lay linoleum tiles:

“You heat the edges slightly, with this here blowtorch” – pointing it directly at my face and nearly singeing my eyebrows –

“then they melt right into place. When you trim ’em to fit those oddball angles, they’ll cut just like butter.” Freddie loved his propane burner,

and he cradled it like a Nazi enamored by a flame thrower. He also used it to melt away decades of lead paint from wooden moldings that ran along the entrances to each room. Being of the devil, he was immune to such toxins, so there were never any gas masks to protect

us.

One day, while we were in the basement rummaging through supplies, he

asked me to hand him a can that was filled with a white powder. When I looked inside and accidentally breathed a bit, coughed, and asked what it was, he matter-of-factly replied, “Asbestos” – as if it were as harmless as plaster of Paris. Then, as we were approaching his car, I noticed that his license plate read 666. This triple six appeared in the center of an otherwise meaningless

series of letters and integers, but it was grouped together

just like that: 666.

When I stopped, pointed, and said, Freddie, look! Six, six, six! he replied, Yeah, so? having no idea what it meant. After I explained, without missing a beat, he grumbled, Yeah,

well … I’m glad I got the devil on my side.

Just when we were kicking

ass on the job, Freddie would say, “Damn, I forgot my Scotch. Robbie, do me a favor, go get it. It’s in the club.”

So I’d climb downstairs,

knock on the door, and tell Nicky or Ralphie or Harry that Freddie wants his Johnny

Walker Black. And they’d let me in, the only nonmobster other than Bonzet who

was ever allowed inside, and hand me a bottle. But always with a sly, witty remark,

such as: Ain’t he had enough already,

or That lush, or Make

sure he don’t drink it all in one gulp!

And I’d smile and nod,

never once talking back to these killers, maimers, and torturers. At first I didn’t

know what they were up to, but I could sense these were not men to be fucked with.

Unless you assumed the proper role – of being the younger, less experienced one,

nodding with respect to the elders – your ass was grass.

As if to illustrate this

point, Dick Bittle, who lived cattycorner to us and whom Drew called Dick Little

behind his back, had once invited his brother, Gary, to visit: a clueless hick

who was a goofball, just like Dick. Drew and I even wondered if Dick had scrambled

his noggin because of his former job: stripping paint from furniture with highly

toxic solvents that eat away at brain tissue and dissolve your humanity faster

than it does the pigment. But then, after we met his brother, we figured it must

ran in the family. In any case, when Gary showed up, he craned his neck back and

hollered for Dick from the pavement. This was before Freddie had installed a buzzer

on the front door, which was normally locked. So Gary was screaming: Hey, motherfucker!

Hey, cocksucker! Hey, you no good little prick!

The men in the club had

no idea who he was, but just as he belted out, Hey, motherfucker!

a woman happened to be passing by. Although these guys entertained some rather

primitive ideas about the opposite sex, they also abided by the Sicilian tradition

of always treating women – at least outwardly – with respect. And, as anyone

in Little Italy could have told you, Gary, you don’t use that lingo in front of

a lady! I mean, that’s somebody’s mother, fer krist’s sake! So they

beat Gary to a pulp. And it made them feel good to punch him in the face, kick

him in the balls, and draw blood, for it was just an excuse to do what they did

best: to break the law and fuck with you for the slightest of reasons – if they

could get away with it.

Anyway, after I’d return

with the Johnny, things would get a bit blurry, if I might call it that. Like

a baby nursing on his mother’s breast, Freddie sucked away at his bottle. Soon,

the tiles would have gotten laid sideways if I hadn’t volunteered, in the most

diplomatic fashion, to finish up:

Hey, Freddie, I’d say,

save your knees, take a break. You’re working your butt off; let Robbie take over.

Come on, relax, enjoy your drink. You did enough for one day. Besides, I appreciate

how you’re teaching me all this stuff, so, let me practice a bit, and get it down.

Freddie would stop, take

a deep, dramatic breath, and say, Yeah, maybe yer right. OK, but do me a favor.

Reach over there, on the floor, behind that toolbox, and hand me one of them cigars.

I’d pass along a cheap

Denobili, and he’d offer me a slug of Johnny, and I’d say No, I’d better not.

I can’t handle it like you can, Freddie. If I do that, the tiles will end up glued

to the wall! And Freddie would laugh, especially since the joke was on me.

He’d imbibe some more,

and start slurring, and that’s when the day would end, the workday that is: about

three in the afternoon, when he’d suddenly announce: “OK, that’s it. I’ve had

too much. We better call it a day.” We’d leave the tools and half-cut tiles right

there, on the floor, then we’d enter his flat, wash up, and go next door to the

club.

Once inside, he’d hand

me cash for a day’s work and insist that I join him in a drink. There was no way

around that, so I’d sip a shot as slowly as I could, because, if I downed it,

Freddie would pour me another, and then another, until I’d be unable to write

for the rest of the day. So, instead, I’d sip and try to blend into the woodwork

as Nicky Joe “The Cook” turned on the espresso machine, and somebody knocked at

the door, and Frankie “The Foot” slid the curtain open just a hair and said, It’s

them fuckin’ junkies.

Two skinny scruffy beady-eyed

guys in their late twenties would step in – but no farther than the threshold

– and open their long trench coats. And just like you’d see in a B-movie, the

linings were stuffed with filet mignon, nicked from a local supermarket. Freddie

would offer them six bucks a steak, then settle accounts and say, Scram.

He’d throw me a steak or two, and Nicky would hand me an espresso, and I’d thank

them profusely but not too profusely: just the right balance. For, as Walt Whitman

says: Be profuse, be profuse, be profuse. But be

not too damned profuse!

Then someone – usually,

the most reptilian creature among them, that being Joey “Guts” – would mutter:

Fuckin’ junkies. I never once saw Joey smile. Whenever he spoke, his eyeteeth

would emerge from the corners of his lips and glimmer, and it was often during

such moments that I felt he only barely tolerated my presence. Whenever he’d say

hello, it was always grudgingly: just a nod or a softly murmured, barely audible,

How ya doin’. It wasn’t merely that Joey didn’t care for me; he was so

profoundly evil that even the slightest expression of etiquette annoyed him. Joey

didn’t really like anyone; he was incapable of liking anything on this earth.

But his greeting, his regard, and his general manner toward me was markedly different

than it was toward the others. More suspicious and begrudging, more reserved and

withheld. For, after all, I’d always remain an outsider; and what the hell was

I even doing there? It was only out of respect for Freddie, who was the alpha

male, that I was tolerated by Joey. Otherwise, I’d have a knee to the groin or

a bullet to the brain.

After Freddie

knocked off his bottle, we’d retire to his apartment. As soon as he grew hungry,

he’d stick his head out the living room window facing the courtyard and yell:

“Oh, Bonzeeeeet?” as if Jimmy were his downtrodden maid or overwrought housewife.

Moments later

Bonzet would arrive, and he’d snap at Freddie in short, clipped beats:

“What the fuck do you want? Why are you always yelling like that? What the hell

is wrong with you?”

Only Bonzet

could get away with that, because he really was a sort of wife to Freddie. And

because they possessed the informality of old friends who had grown up on that

very street. And because he was, after all, not the slightest threat. So, Freddie

enjoyed cranking him up and bringing out his hysterical side, and that’s why Freddie

put up with it.

Once Jimmy

had simmered down a bit, he’d turn to me and nod: a warm, benevolent, respectful

nod, and maybe murmur How ya doing, Bobby?

Then he’d unstack the aluminum pots and pans and begin his elaborate preparations.

And it was more like what you’d cook for a regiment. You’d never imagine that

it was just Freddie, Bonzet, Peggy, and me. In one of those gleaming vat-shaped

containers, Bonzet would boil water and toss in ears and ears of corn. After unwrapping

the filets, he’d heat some tomato sauce in another pot filled with mushrooms,

red and green hot peppers, and everything Sicilian imaginable.

As I said to

Drew, try as we might, it was as if we could never escape Gravesend. There we

were, more Sicilianized than ever, and there was no avoiding it. Because, after

all, you can’t just walk away from the Mob or from men like Freddie. But, at the

time, we hadn’t yet realized how deep into this mobster mire we’d sunk.

After our filet,

baked ziti, or chicken parmigiana, or, I should say, during it, there would be

knock after knock at the door, with Freddie barking who is it? and someone answering

Paulie, or Tiny, or Ralphie. Then Paulie “The Pipe” or Tiny “The

Ton” or Ralphie

“The

Rope” would saunter in and hand Freddie

a piece of paper marked with a number, along

with some cash.

Freddie would

nod his head and make

small

talk with these goons as Jimmy

and I devoured his delectable spread. And

I’d say Bonzet, this

is magnificent; I can’t

believe

how good

this

tastes. Then

he’d

assume his

most

serious demeanor, because

now we were talking about that

most holy of holies. With a concentrated look

on his face, he’d hesitate a moment,

as if gathering

his thoughts and searching for words, words

usually being

so unnecessary to

Jimmy. For who

needed

them when, instead, you

had sun, wind, food,

drink,

and life itself

right there, in the palm

of

your hand? But eventually he’d

say,

“Bobby, it ain’t hard. This

is what you do.

You boil

some water …” Then

he’d

spend the next

twenty

minutes describing,

in minute detail, how he’d prepared the filets, or

the

mushrooms and tomato sauce,

or how to

chop garlic, or

what to look

for

when you

shop

for red and green hot peppers.

Freddie would

finally lose his patience and

shout:

“Bonzet, what the fuck are you

wasting

yer time for? Robbie

ain’t never gonna cook nothing

for

himself! He’s

an

upper-class man! He even has a college degree!

And look at him

now!

He’s working for me!

What does that tell you,

Robbie?

What’s more important, book knowledge

or

life knowledge? Nothing

beats real experience

…”

But

the “experience”

Freddie was jabbering

on

about had nothing to

do with what my Uncle

Byron had meant

when

he’d watched me complete my first oil

painting when I was six years old and said,

Robbie, you’ve had

a new experience.

Instead, it had to

do

with incarceration in Sing Sing, or

the Tombs,

or

wherever Freddie had

slept behind county walls.

Freddie

never

spoke about

being in the

Mob. He

even tried

to lead us

off

the trail, making a

seemingly innocuous remark

about how, once, he’d met a guy

who had seemed to be in the

Mafia. A red

herring if there ever was one,

as I later

realized. But he made no

bones about

how he’d

done time for various crimes. In

fact,

he was proud of

it,

as he knew

it

would only bolster his image

as a tough

guy.

Freddie often

taught me peculiar little things, odds and

ends

that he’d learned in prison. One afternoon, while we were looking

for

a nut to fit a bolt,

he grabbed the tray inside his long

metal

toolbox,

which was filled with

a heterogeneous assortment of orphaned nuts,

bolts, nails, and screws, and said,

Hey, grab that there paper! meaning a copy of the Daily News

that was lying on the floor.

After spreading the paper open,

he dumped

the contents

of the tray onto the centerfold. Poking his

knobby

fingers

through the mess, he

finally found what he was looking for.

Then he carefully gripped the paper by the edges, forming a funnel, and poured

everything back into the box, minus any mess.

Smiling his

mean but wily grin – his diabolically

charming yet unquestionably pathological

smile – he blurted out: “Let me ask

you

something. I bet

you never

learned how to use a newspaper like that in school,

did you? Well, you know

where I learned that?

Same place where I got all my best education.

In the can.”

One evening, in the midst of an unspeakably

delicious feast of calamari and sautéed garlic, a Longshoreman named Eddie “The Breeze” showed up. Eddie was distraught because even though the guys on the job had pooled their resources and played a winning number, he’d scrawled it so carelessly that it resembled a 451 instead of a 431, so now the numbers men refused to pay up.

To make matters worse, the Longshoremen were convinced that Eddie had pocketed the prize and was bullshitting about not getting paid because of an ambiguous scrawl.

So there he was, bug-eyed and pale as a specter, as we ate our corn on the cob smothered with nature’s best butter and glistening with heaps of salt. As it melted in our mouths and I complemented Jimmy on his cooking, Eddie, who was accompanied by a tall, strapping Longshoreman named Ronnie,

said that the guys had nearly lynched him when he claimed that he hadn’t collected anything. That’s why he was there now, with Ronnie, so that Freddie could explain what had happened and they could receive a final verdict about what the “numbers guys” at the top had decided to do, since they, the Longshoremen, still felt they should be rewarded.

“Because, Freddie, remember when I gave

it to you? I even said, ‘431, Freddie, I’m prayin’ for it: 431!’”

But Freddie,

who treasured the opportunity to lord it over other

men, especially when they were three times his size, was in no

rush. In

between succulent bites

of calamari

he’d pause, burp, and savor each morsel of

his story, recounting how he’d gallantly

strolled into Mikey

“The Meat

Hook’s” office and explained: “Mikey,

these

Longshoremen are stand-up fellas.

We’ve been

doing business with them

for years,

and they never pulled

nothing like this

before.” To give Mikey an idea of what an

exemplary character Eddie was, he added that whenever Eddie came

in with a number,

Freddie would invite him

to

sit down and have a shot of Johnnie. But Eddie

was

a good, respectful

man who always politely declined, knowing

how busy Freddie was and how inappropriate it would be

to

take too much of his time.

Mikey

interrupted and said

never about mind that bullshit. What happened? When

he handed it to you,

did you

look it over or

not? And if you did, why the fuck didn’t you ask, What is this; I can’t read chicken scrawl!

You sayin’ 431

or 451?

And Freddie said, Mikey,

I didn’t ask nothing because Eddie said, “Say a prayer

for the 431! If

I hit

it, I’m taking

Suzie”

– that’s his wife – “out on a cruise.”

Mikey

drilled his eyes into Freddie and said, You sure about

that?

Absolutely.

He repeated it twice:

Pray for the 431, Freddie!

Mikey

glowered

but then smirked, scratched his chin, spit

on the

floor, lit a cigar, and asked

Freddie

if he wanted one. But Freddie said, No, thanks;

I’m

good.

“Because

Mikey

loved them fucking cigars.

They were like

fifty-dollar Cubans. You ever

smoke a Havana, Eddie?”

By

now, Eddie was nearly crawling through his

skin. He was sweating

like a pig, and not

a pig in shit

but one

about to

get roasted alive. Then

Freddie looked up from his plate and said, Hey, you sure you

don’t want no

calamari? And Eddie

got so choked up that he

couldn’t talk. He just shook his head,

no, while his

partner

stood beside him,

mute. Eddie must have told Ronnie not to

say a word, because he

knew Freddie hated to converse with strangers.

So Ronnie just stood there quietly and

turned a deeper shade of red, and I don’t

know whether

it was from fear or from anger.

After

letting go a long sonorous burp, Freddie wiped his chin, made like he was about

to reveal the final decision, then turned to me and asked if I wanted to

watch Buck Rogers in the 25th Century or

I Love Lucy.

I

said, “Let’s go with Buck,” so Freddie hit the

TV zapper

just as Buck was just coming

on. And we both agreed, Freddie and I, we always

agreed that although this Buck was cool, he

wasn’t as cool as the original one from the Thirties. How

I loved to watch

the old Buck Rodgers and

Flash Gordon serials! With

those ancient black-and-white shows, everything was so obviously

faked. The sets

were constructed of paper-mache and cardboard,

and

sometimes they’d shake – just as Eddie was shaking

now – while

Flash or his angelic heartthrob, Dale

Arden, ambled across

the stage. But the best part was

the spaceship, which sputtered like a sparkler

and moved so slowly and in such a wavering, crooked line that it looked as if

it were about to fall

from the sky at any moment.

Yet

there was something

terrifying about those old

tales, because people were always getting killed: even

the main characters,

whom you’d never

expect to get offed. But

they were captured

and zapped

by aliens

who

appeared at

just the wrong

moment. Thus, there

was something so

lifelike

– or deathlike –

about Flash

Gordon and Buck Rogers. It was just like the Mob. One

wrong move,

and it didn’t matter

if you

were Joe Blow or Mikey the

Meat Hook, you were gone

– poof – just as quickly as Flash’s

comrades were vaporized by those guns.

After

swallowing one last chunk of calamari, Freddie

burped,

farted, said

Excuse my manners, then looked Eddie

straight in the eye and

grumbled, “Listen.

Mikey said: ‘Next time you write

a three, make sure

it looks like a

fuckin’ three.’

But for now, you’re good.”

Meaning,

the Mob had

decided to fork

it over.

Eddie’s

eyes popped, then rolled across the

floor. He could barely

contain his joy,

or greed, or whatever

the hell it was.

When

I consider it now, years later, it’s amazing how unabashed Freddie was about that

whole numbers racket. At one point, they’d even positioned a kindergarten chalkboard

right in front of the club, where they’d draw in the digits as soon as they were

announced. But according to Bonzet, the cops finally told them to be more discreet,

so the blackboard was 86’d.

It

wasn’t just the numbers

that made us suspicious of Freddie, who claimed he was handling it as a favor

for one of the local tough guys. What really did it was a story that he related

one night when Drew, who occasionally worked with us on bigger jobs, was

seated beside me at Freddie’s kitchen

table. We

were savoring

a cheesecake that Freddie

had portioned into

what he

called humungous

slices, passing

it round and round until we could

eat no

more.

I

can no longer recall how we drifted into

this horrendous tale or what, exactly, the

segue had been.

But whatever it

was, Freddie had been drinking

too much

and had let it slip that, a few years

before, his sister, who lived

in L.A.,

had phoned to complain

about her neighbors: a free-loving – in every

sense of the word

– couple. What nowadays

we’d call

a New Age couple perhaps, but

the main point being

that they were

nudists.

Although she’d

politely asked them

to erect

a fence so she wouldn’t have to see them

and their friends cavorting around naked

in the

yard, they did

nothing; they

refused.

So

Freddie said, alright, sit tight, I’m

coming over. And

he flew

to L.A.,

and he set

their house on fire.

After

he returned, he

phoned her,

as per arrangement, and asked, “How’s

the barbecue coming along?”

“Everything’s

turned out

to perfection.” And they laughed, and that

was the end of the

freewheeling couple.

Upon hearing this, Drew

and I shot each other a look, and we

nearly gagged on our cheesecake. But we carefully masked our shock until Freddie had gotten up to pee – “To relieve myself,” as he said, with faux diplomacy.

How Freddie loved to display his “manners”! When he lived in California, he worked in the film industry – the porno business, to be precise – and he’d hobnobbed with some wealthy businessmen in L.A. Unlike the other

low-level hoods at the club, Freddie knew more about the whole class divide and how the well-to-do speak differently and carry themselves more gracefully. So this was Freddie’s sardonic way of saying, Yeah, sure; I could do that too. But fuck it, and fuck you …

We never

learned if the

nudists had been hurt in the blaze, and, to be honest, we didn’t want to know. But, at that moment, we realized we needed to distance

ourselves.

A few days later, Freddie came up with the idea of taking me to

a bordello – a proposition I successfully managed to avoid. And whenever he brought

it up, he’d make odd remarks about male anatomy: something that seemed a bit out of character, but eventually it fit snugly into the Freddie jigsaw puzzle.

Freddie later confided in me that, when we’d first moved in, he’d assumed Drew and I were a gay couple. It wasn’t until my Ethiopian girlfriend, Abebe, showed up – a moody,

brooding statuesque lady with black fire in her

eyes and an enigmatic

smile on her lips – that Freddie realized we were just “regular guys.” Yet, he related

this to me with a lingering tone of uncertainty, as if hoping that he might be

wrong.

One night when he was really hitting the bottle, Freddie insisted that

I accompany him to his other flat. This wasn’t his usual digs but was located in a building a few doors away, where he’d grown up with his

immigrant parents.

As is often the case

with mobsters, Freddie regarded his mother as an unblemished saint. His eyes would

tear at the mere mention of her name. And, of course, prominently displayed on his dresser, there it was: a photo of the most hideous woman I’ve ever seen.

Freddie’s mother closely

resembled the iguana-eyed matriarch who stars in Lina Wertmüller’s Seven Beauties: an obese Nazi who runs a concentration camp. The story revolves round a handsome prisoner, Pasqualino, who decides that the only way to escape is to seduce her. But when she sits there naked before him – with a grave, unsmiling expression, and with

all the allure of a hippopotamus – he can’t get it up.

Just

as one might attempt

while studying

a portrait of

Hitler’s mother, I scanned the image for a detail that might reveal an essential

link between the beast and the diabolical

runt it had spawned. As I continued to gaze,

she seemed to scowl, her ebony eyes afloat in a vat of pale, jelly-like flesh.

Garbed in

woebegone widow’s

attire, she appeared like a black widow

spider that had

just swallowed her son’s meager soul

… and was about

to vomit

it out

at any second.

A

final overlay of hideousness I have yet

to mention. As I later learned from one of the old-timers on the block, the spider had died a most fitting death:

One

day, a garbage truck

had come careening round the corner. A heavy metal

chain, which was normally attached to

each side at the back of the

truck, had slipped off one of its hooks.

As it flew out,

unfurling across the street, it wrapped itself round Freddie’s mother’s neck.

Then it lifted her up and snapped her back, into the gaping maw where the

trash was churned and crushed

to a pulp, which is precisely what it

did to her.

All this filtered through

my mind in brief, fleeting moments as I stood there and Freddie muttered: Yes,

it was a picture of his mother. Then he stepped into the kitchen to pour himself

a bumper glass of Johnny. When he returned, after hemming and hawing and acting

a bit more distracted than usual, he said, “You know, it’s late. Why don’t you stay over? Here, you can sleep in these” – handing me a pair of silk jammies.

And, oh, boy; all at once it hit me, naive little bunny that I was. Freddie’s gay. And

he wants me to be his chicken. And that’s what he learned in the can …

Of course, I scrammed. Then

I really distanced myself, working as little as possible until I found a construction

job that paid more, and I had a legitimate excuse to move on.

* * *

About a year

later, as I was walking along the block one evening, Freddie waved at me from the driver’s seat of his black sedan,

which was idling near the club.

He said that

he’d just sold the building and was about to move into his mother’s old flat.

“Call this number,” he added, handing me a scrap of paper. “It’s the Manhattan

housing authority. Tell ’em you’re being overcharged.”

We’d always

assumed that Freddie was ripping us off, but we never dared to mention it. But

now, he was giving us carte blanche to do as we pleased and to take the new landlord

to court.

It was his going-away gift.

Freddie continued to manage the club for a few more

years, but then, shortly after I left for Paris, he moved to California. A smart

relocation on his part, because the Feds came down hard on the Italian Mob in

New York, no doubt to make way for the more powerful Russian and South American

gangs.

But one thing Freddie couldn’t escape was AIDS.

I didn’t hear about it till decades later, but that’s

how he died. Especially at that time, when the illness was newly discovered and

the treatments were harsh and ineffective, a bullet to the brain might have been

more merciful.

When I learned of his demise, I tipped my hat to Freddie: son of proud immigrants, and the craziest motherfucker on the block.

____________________

Copyright © 2012, 2018 Rob Couteau.